Ethiopian Utopia has a nice ring to it, and after discovering it wasn't a mythical place, I was keen to find out if the reality was as good as the pleasant rhyming couplet. Whilst waiting for the visa machine to churn out our valuable travel documents in Addis Ababa, we had begun making plans for the rest of our time in Ethiopia, and accidentally discovered the existence of a small community which had been founded by a single man trying to make the world a better place.

Zumra Nuru is a fascinating man by any standards. At the age of two (so the story goes) he began to question his mother about the inequalities he saw all around him. He wanted to know why men and women were treated differently, why work wasn’t shared equally, why people were persecuted for their religion or ostracised because of disability, and why young people didn’t have a role in society. Not finding the answers in his village, and upsetting several people along the way with his questioning, he set out to find out the answers for himself. Whilst travelling throughout Ethiopia, Zumra didn’t find any answers, but did find a small, loyal following of people who agreed with his ideologies, and between them they founded the Awra Amba community on a small piece of land just east of lake Tana.

The founder of Awra Amba - Zumra Nuru as depicted on the wall of the community museum... (Photo Credit: Nick Colwill)

Far from being the end of the story, in the 37 years of its existence, members of the Awra Amba community have had to endure violence and persecution, being labelled as dangerous extremists, having their land confiscated, droughts, economical poverty, and being arrested. Fortunately, the perception of the community is changing, and more recently it has been publicised as a sustainable approach to modern living, and a beacon of tolerance in a broadly intolerant society.

Getting to Awra Amba was part of the appeal, given that its location is best described as ‘off the beaten track’. After the usual arguments at the bus station, negotiating prices and reclaiming our luggage from over-eager teenagers, we were able to secure a bus from Bahir Dar heading east. Without hesitation, our bags were tied to the roof, and we folded ourselves into a minibus ready for the mercifully short journey. Peering out of the tinted windows of what apparently was a nightclub on wheels, the rapidly moving scenery was yellow and dusty, punctuated by huge piles of freshly cut grass eagerly watched over by thirsty looking men and their oxen. The road was modern and smooth, and after only an hour we found ourselves being disgorged by the driver who, after a bit of persuading, had agreed to drop us off seemingly in the middle of nowhere, with the only discernible feature being a small, dusty track leading away from the dark bitumen.

Fighting for legroom - a practice we became well versed in...

The bus sped off leaving us in a cloud of dance music and dust. As the beats faded we relished the peace and quiet of this seemingly uninhabited corner of Ethiopia. Next to the track was a small, rusting metal sign pointing in the direction of Awra Amba, and so we shouldered our bags, and began walking towards the village which the sign optimistically told us was a mere two kilometres away. It felt good to be walking in the countryside again; after a few weeks of developing a caffeine addiction in the hustle and bustle of Addis Ababa, the dry but fresh air energised us; it was good to be moving freely again. The late afternoon sun was still hot, and within minutes we were sweating in the dry, dusty heat.

Within half an hour, another understated sign told us we had arrived in the village. The well-worn road penetrated deeper into the village, weaving its way between neat wooden framed houses, all walled with dry mud, and roofed with matching corrugated metal. The neatness of the village was immediately apparent, and the uniformity was pleasing on the eyes. The village was peaceful, and sporadic villagers were relaxing in the shade of the plentiful trees, we weren’t really sure where we were going, but decided to adopt the same shade utilising tactic, and spied a particularly large tree in what seemed to be the centre of the village, and stopped to take advantage.

Beautifully indecipherable Amharic...

Awkwardly shuffling our feet and not really knowing what to do, we were eventually approached by an elderly gentleman with a kind face, who pointed us in the direction of the large meeting house, which upon reflection would have been a much more obvious place for us to have aimed for. Inside the simple mud-hewn building the air was cool, and we were ushered to sit on the ingenious raised seats around the edge, their muddy origins covered by intricately woven palm mats. Almost immediately after sitting down, a man appeared from a previously unnoticed doorway, offered us coffee, and introduced himself as the village tour guide.

Suitably caffeinated, our guide began to explain a little bit about the ethos of the village and the community which had built it. Fundamental to the ideology of the community is equality; there is no caste system here, no racism, and no sexism. Everyone is equal, and has a role to play, as any discrimination threatens the productivity of the community.

The community is organised into various committees who oversee everyday functions and activities: there is a rules and regulations committee, a hygiene and sanitation committee, an education committee, a guest reception committee etc. you get the idea. (There are even more committees here than in Tuvalu during the lead up to the Royal visit - something I never thought I’d see!)

Perusing the mud shelves of the community library... (Photo Credit: Nick Colwill)

You have to be democratically nominated and elected to be on a committee, and then you serve for three years, when the process is repeated. One of the most important committees allocates the communities’ work force to the various jobs which need doing - farming, weaving, running the small shop, and showing tourists around. The jobs depend on the current need of the village, and can change daily, they are also divided along lines of competency, not gender - there is no such thing as ‘men’s work’ or ‘women’s work’ here.

The most surprising aspect of the community is their attitude to religion. Throughout the rest of Ethiopia, daily life is dominated by either Orthodox Christianity or Islam, this had been starkly obvious the previous week when our bus was delayed for hours as it followed a lengthy Orthodox procession through a series of small towns to celebrate Timkat, the most important of Ethiopian festivals. The community are not religious, but do believe in a creator. Being created means each community member is inherently sacred, meaning that any worship that takes place should only be done privately inside the individual, negating the need for religious buildings or ceremonies; simply, there is a belief that you have been divinely created, and are therefore sacred - a simple and beautiful concept.

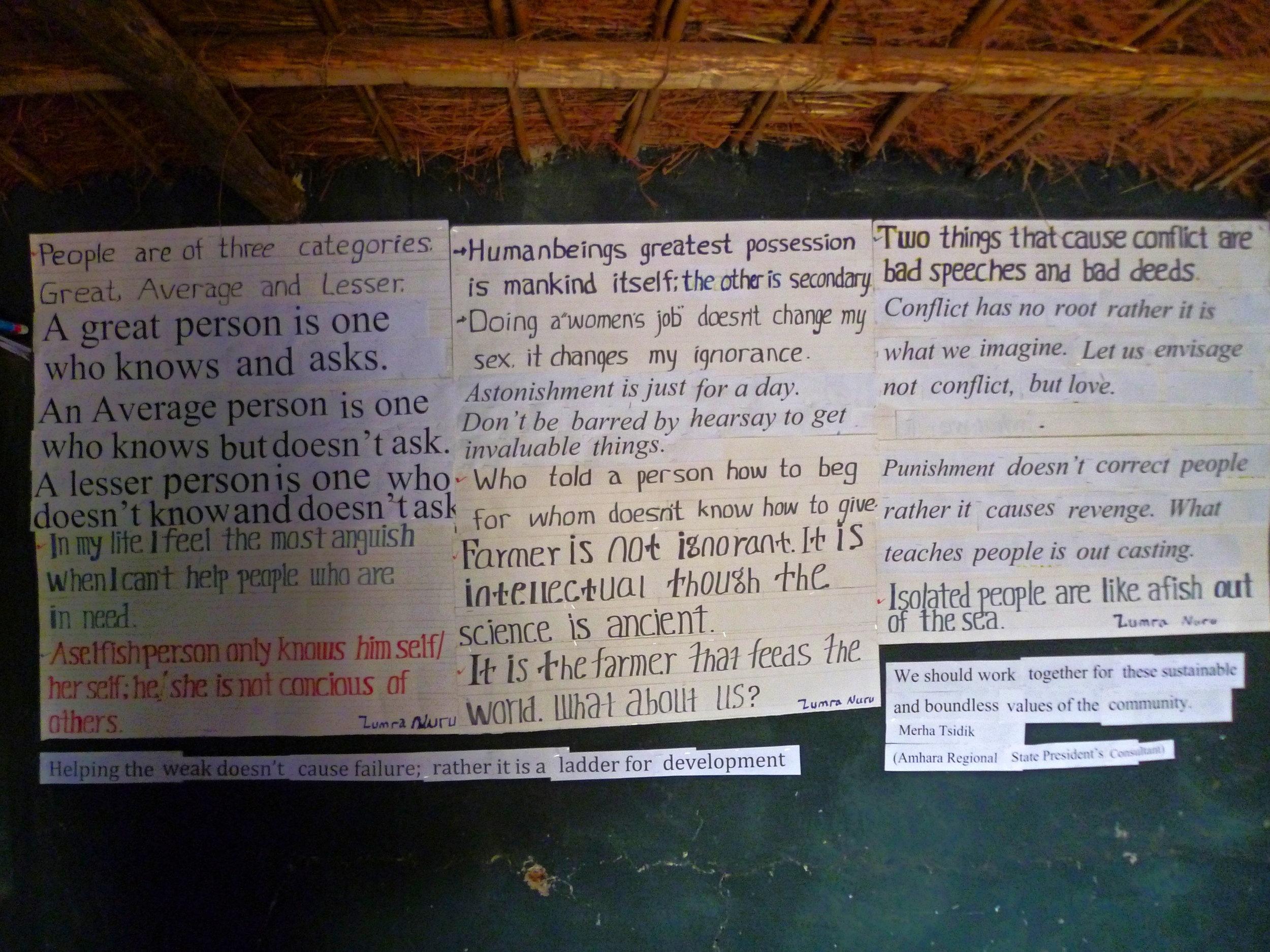

Some of the community beliefs proudly displayed at the community kindergarten...

The community practices what it preaches, and as we began our tour of the village, it was clear that equality abounded – the uniformity of the houses allowed the communities’ limited space to be utilised efficiently, with shared spaces taking pride of place. After a quick look at the museum proudly displaying the communities’ core principles and newspaper cuttings from dignitaries and religions leader, we were invited to look at the kindergarten and library where we struggled to get to grips with the Amharic alphabet. The community has allowed a government school to be built on its land to allow their children to receive a state education, but their kindergarten is run for and by community member only.

Next on the tour was the old peoples home, where the community take it in turns to cook and look after its elderly and infirm – an impressive building, once again beautifully built utilising the materials found naturally, the inside is divided into individual bays allowing everyone their own space and dignity. This clever use of space was echoed inside the local houses where incredibly impressive hand built stoves (apparently designed by the founder) allow the homes to remain clean and clutter free, but retain their utility - a beautiful piece of engineering and design.

The simple and functional community kindergarten...

Wandering around, the tranquillity was unnerving, and it took a while to get used to our anonymity again, here we weren’t viewed as wealthy tourists with bottomless pockets, we weren’t seen as potential scam targets, and we weren’t seen as novelties to be pointed at and discussed. Instead, here we were simply human beings, deserving of the same respect as every other human being, it was as refreshing as it was profound.

Sunlight pouring through the workshop windows illuminating the intricate Awra Amba weaving...

Our final stop was the cooperative workshop which housed dozens of looms, and several wool spinners, the main income stream for the community. Being a Sunday, the workshop was empty and the mighty machines stood silently mid-weave as a proud symbol of community endeavour and creativity. Whoever first developed the loom must have been a genius or a sadist; they are so wonderfully intricate, and the designs they are capable of creating so varied, but they are oh so complicated! Confidently I took my seat after being shown the most rudimentary of movements, but within seconds I was in trouble, and scared I had ruined hours of work, I humbly left the loom, upon which my pitiful efforts were put to shame by an elderly gentleman who when not napping in the corner of the workshop as he was today, is able to produce 30ft of woven material in an eight hour work day – very impressive when you consider all I managed was a tangle of thread and wood.

Next to the workshop was the village shop where you could buy some of the weaving, at an incredibly reasonable price considering the work involved. I bought a beautiful scarf and we both decided to buy a large blanket each, thinking ahead to the potentially chilly desert nights we were heading for in a few weeks.

Tour complete, we relaxed for the remainder of the afternoon, drinking coffee and absorbing all the information we had been given. As the sun began to set we feasted on injera with mixed sauce before deciding to get an early night. We were shown to the simple but more than adequate rooms, which like everywhere else in the village, were intricately made from mud and straw. The simplicity was very appealing: bed, mattress, blanket, desk, candle; what more do you need?

Beautiful, timeless machines...

That night I lay awake in my comfy bed, watching the light from a single candle dance across the simple mud walls, with only the sounds of insects chirping outside to break the silence. I had spent the day listening to how a small group of people with the simple belief that we are all equal, have been able to, despite a wealth of challenges, create a community which promotes acceptance, and equality. With all the intolerance and hatred in the world, Awra Amba stands as a beacon of hope, demonstrating that with the right ideology, living successfully with fellow human beings is a reality, not just a possibility.